Embodying the Spine in Movement and Stillness

PART 1: Finding Spaciousness and Ease in the Spine

What does it mean to truly live in your spine — not just to study it, but to feel it as a living, intelligent, and spiritual center of your being?

This is the first part on an ongoing investigation of our spines from a new perspective. We’ll look at the anatomy, movement, and inner experience of the spine — from our very beginnings all the way to a fully developed and well supported adult spine.

Fully honoring what we already know about the anatomical structure of our spine, we ask questions. We simply say, “Yes, I see that… and what else is true here?” Our approach builds on the objective knowledge as we move toward a fuller embodiment of this core structure.

We find doors to inner sensing and feeling. We discover the gifts that a fully known and embodied spine carries for us in our lived experience. Yoga is a great framework for exploring the inner world of the spine because Hatha Yoga’s practices are already organized around the spine.

The Spine as Core Axis in Yoga

Hatha yoga is a spine-based practice. It is organized around the esoteric recognition that the three major nadis, or life-force channels—ida, pingala, and sushumna—are contained within the spinal cord. These are subtle energy channels. They can’t be seen with microscopes, and yet they are felt and known in the inner subjective experience of yoga Rishis (seers) and adept practitioners over eons of time.

According to yoga physiology and subtle anatomy, ida and pingala nadis relate to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, respectively. Sushumna nadi, at the center of the three, provides our individual access — direct connection — to the source of our being. Sushumna radiates the light of pure being-ness through all aspects of who we are, while ida and pingala nadis carry and express the qualities and traits that make us individual and human. We are all different in our expression and the same radiant potentiality and presence at our core.

Nice organization right?

All of the practices of Hatha Yoga are ultimately directed toward balancing these energy channels in the spine in order to calm the fluctuations living humanity — ida and pingala — long enough to recognize the radiance that underlies it all, our core of cores —sushumna.

In postural yoga, we study the spine for its importance in to assisting the even and unobstructed flow of the life force within its structure. We study the discs, bones, ligaments, and their muscular supports. We look to maintaining a safe home for the central nervous system as it flows within the vertebral canal.

Skeletally, we define our spine as axial (core) and all other skeletal bones as appendicular (peripheral)1. In Embodyoga we often refer to “core and periphery” as ways to differentiate sushumna’s embodied radiance — how the light of awareness spreads in the body — from our personal qualities and traits.

Functional Anatomy of the Spine in Movement

As yoga practitioners we find it interesting to inquire into all that it means to live in a body that is organized around a multilayered spinal system that contains everything from the most refined energy and awareness possilbe to the most dense structual aspects of form. Our spines contain the seed of every aspect of body, mind, spirit. In yoga we perceive that all the information for a human being is included along its length. There is so much to look at. In this piece we will look at structure and means form maintaing good support for our core body and its critical structures.

Some of the things we look at here for application in our movement practices:

Maintaining a Calm & Mobile Spine—both for experiencing a unified sense of body-mind, and for remaining irritation- and injury-free in the spine by avoiding shearing lines of force across it at any point.

Exploring the felt sense of spine as core.

Understanding all variations of movement possibilities in the spine, how to put them together in whole-body movements.

How consciousness and movement interface. How consciousness changes movement and how the mover is changed by consciousness.

Practicing all directions of spinal movement in all relationships to gravity for cultivating a balanced body and mind.

Understanding how core body awareness affects our spinal curves.

Differentiating core from periphery in body and consciousness

Finding the unity of core and peripheral body at the physical, energetic and spiritual levels.

The curves of the spine are designed to distribute forces and absorb shock. They especially offer resilience to our core and sense of self. In health, the spine is a fantastically mobile, supportive, and intelligent central structure. Our central nervous system is safely contained in the vertebral canal, protected by the vertebral bodies in front and by the transverse and spinous processes behind.

When our spinal curves are not balanced — which is common due to our cultural movement patterns — forces begin to flow in ways that wreak havoc with our spine’s elegant form and potential. When body tissues are having to do work they are not designed to do, they cannot not do a very good job of it.

Spinal ligaments can harden and become brittle. Alternately, they can become overstretched and no longer able to support the bones and joints in the way they are designed to do. Then, our muscles will need to brace. Discs can compress and even be squished outward from their home between the bones. Disks and bones may eventually degrade. The whole thing has the capacity to create quite a mess, including a good deal of discomfort and (too often) outright pain.

Widening Perspective and Soft Strength

A mobile core-body and easeful spine is the result of — and profoundly effects — how we feel and move in the world. The difference between a frozen or mobile core is directly related to how we move in our bodies—and to how we think we can move.

Natural resilience and ease are based on a lot of things going right in the body. Increasing our understanding of the dynamics of the parts and the whole, and how they work synergistically, can help us to improve our own experience of what it means to move with integration and ease.

Wouldn’t it be nice to feel really good in your spinal core body?

Not all spinal movement is the same. We can all flex, extend, twist, and bend to some degree or another. But is it really a “spinal” movement we are after? I would say not necessarily. Perhaps we are also after a movement of consciousness, focus, and attention. Perhaps we are turning or bending out of curiosity, celebration, or desire. So many different ways to express spinal movement and each of them has the opportunity to have the full support of body, mind, and consciousness.

Every movement involves a wholistic symphony of actions. We do not just move from our spines! Our spines rely on the resilient support from all of its neighboring soft tissues. Far from alone, spinal movement is always in active relationship with the whole body. Its support can be very deep. Or, it can become isolated into the column itself, which runs the danger of creating hardening in all of its structures.

Let’s see how we can increase our spinal integrity and comfort by shifting our perspective slightly. Let’s take a wider lens to the subject and see what we find.

Movement Patterns Begin in Infancy

As babies, our bodies are just beginning to set up patterns of movement and support that will last a lifetime. How we are moved by our caretakers, and how we are placed to play, lays down internal organizational patterns that continue through a lifetime.

When, as babies, we are encouraged to play on their bellies, critical patterns of support have the chance to naturally arise. These supportive templates layer one upon the other as the baby plays and learns.

These movements are much more than musculoskeletal actions.

Our babies are developing organ tone.

They are learning to take support from the earth and to rise up out of it.

As their movement develops, so do their spinal supports and curves.

Their nervous systems are integrating sensing and feeling through their whole bodies.

Their fluid — cellular and fascial — organization is taking shape.

Their entire being is becoming coordinated and unified in its function.

Belly play as babies has everything to do with the development of a healthy spine.

It is never too late to get down on the ground and play! These supports are still in there waiting to be discovered and engaged.

Not all of us were lucky enough to develop these inner support templates as babies. Perhaps we didn’t get much time to play on our bellies. That’s okay! It is never too late to bring these patterns into your body. Yoga lends itself to stimulating the intricate and powerful weave of these patterns into expression. Explore in this previous post:

As adults we can explore these latent waves of support and stimulate them into action. We get down on our bellies — we move, breathe, and play. We pay attention and feel what we are doing as we do it. What we find so often is that as we take our time and explore, our bodies respond with an increasing sense of integration and ease that is new. It’s in there… waiting to be touched and stimulated into action. All we need to do is take the right direction in practice… and “play with it”.2

From Block-Stack to Tensegrity

Our concepts of anatomy also dictate the range of possibility that we perceive to be available to us in our spines. For so many years, we have assumed that the vertebral column takes and distributes its weight directly through the bones and the discs. We have called the vertebral bodies the "weight-bearing bodies of the vertebrae,” and we have imagined our spines as structures designed to bear the body's weight, straight down through our stacked spinal bones, and into the earth.

The spine has been viewed as a stack, or column, of blocks: each vertebra resting one upon the other, cushioned by shock-absorbing discs. When we look seriously at how to maintain the health of the spine from this perspective, it is hard to imagine how we can actually keep from seriously compressing the bones and damaging the spinal discs. In fact, what we see is that the spinal bones and discs do degenerate significantly with lack of integration and fluidity in movement—not to mention the effects of aging on our embattled spines.

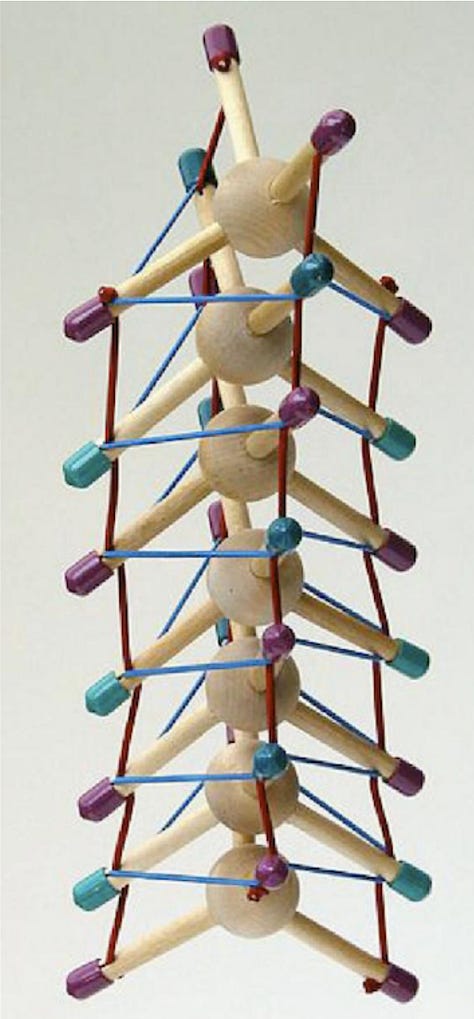

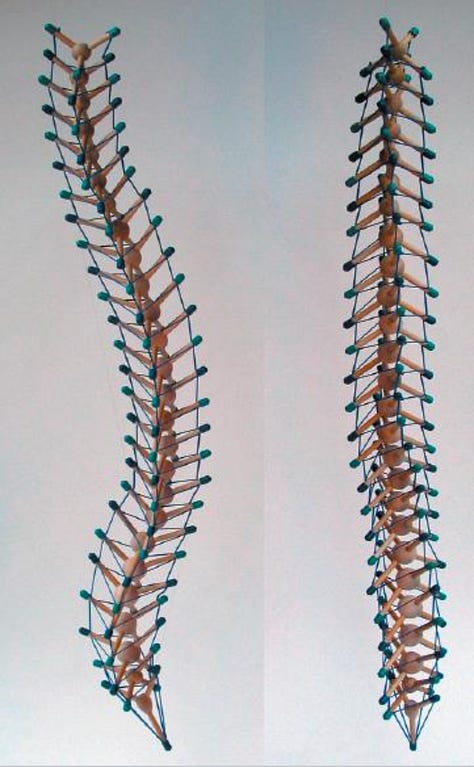

A newer perspective is one of viewing our bodies—and all of biology, for that matter—as tensegritous structures. Tensegrity structures are built through a balance of tensioned and compressed parts. In observing biological organisms, from the most minuscule to the enormous, scientist have found that all biological organisms are made strong and resilient by their tensegritous unison of tensioned and compressed parts. Tensegritous structures work just as well in any relationship to gravity, making them very useful as biological forms.

The effect of tensegritous integration is that forces are distributed wholisticly. No one part is responsible for bearing the entire weight of anything else. Forces are distributed throughout the body, creating much more overall strength and resilience than would be possible with the old paradigm of block-upon-block being held to the ground by gravity.

We Are Biotensegritous Beings

Biotensegrity is tensegrity applied to all living organisms.3 It is becoming more common in science to recognize these same these same tensegrity shapes and dynamics in living organisms. Especially in areas like cell biology and biomechanics, it is increasingly common to recognize and utilize the concept of biotensegrity.

From the smallest molecules, cellular components and membranes, to our larger musculoskeletal selves we are biotensegritous fluid beings. From the smallest to the largest and back again we are intimately relational and universally supportive of one another.

Spinal Tensegrity

Bones and discs are not alone. The muscles and ligaments, even the surrounding organs and glands, are part of the biotensegriy that supports our spines. In this model we begin to get the idea of how our spines might be suspended, rather than stacked. It is a complex matrix of support.

The firm elements are the bones, and the elastic tensioned parts are our various soft tissues: ligaments, muscles, fascia, etc.

This is an important shift in relationship to how we have viewed the spine.

In tensegrity structures, bones don't touch. In our spines, the bones essentially float on the discs. Discs have the freedom of movement that they naturally desire, as they are not being overly-compressed by the bones above and below.

This paradigm of organization of our vertebral column is critical to the new understanding of how to keep excessive forces out of the major joints in yoga—and, in this case, out of the spine itself.

Spinal Tensegrity in Practice

When we practice spinal movement from a tensegrity model we find the experience of spine becomes thicker (not just the bones anymore) and more fluid. The neighboring soft tissues are equally involved and bring a sense of elasticity — strength and resilience — to this whole region. We feel actual space. Realizing that it is not just the vertebral bones that are performing our various spinal movements, we find that the entire fascial weave of the central body is involved in maintaining the sense of ease and mobility in our spines.

It is quite delightful and freeing to what may otherwise be a very linear approach to spinal movement. Instead of feeling like we have to “hold ourselves up” we begin to feel suspended, buoyed, and dynamically connected. Gravity becomes a partner, not something to overcome.

Part 2 of this series takes us into the developmental foundations of our spine. How they grew and what that offers to our adult movement now. Read it here:

Share these articles with your friends? I appreciate it very much!

Still considering becoming a paid subscriber? Do it! It really helps! It raises my spirit, and keeps me going!

And, if you would be so kind…click the like button at the bottom of the page.

Thank you all so much for being here!

More coming soon,

With love,

Patty

In Embodyoga we often refer to “core and periphery” in the body as ways to differentiate our essential nature from our personal qualities and traits. Core is essentially sushumna — empty radiance itself. Our individuality arises from the duality and the play of ida and pingala nadis. Loosely, we can consider “spine” as core and everything else as periphery.

Are you interested in recorded or live video to explore these patterns? Let me know and I will put that together. Meanwhile, I recommend two excellent books:

Basic Neurocellular Patterns: Exploring Developmental Movement by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen

On the Way to Walking by Lenore Grubinger

Dr. Stephen M. Levin coined the term biotensegrity in the mid-1970s.