The Architecture of Living Form

Tensegrity, Consciousness, and the Fascial Web of Support

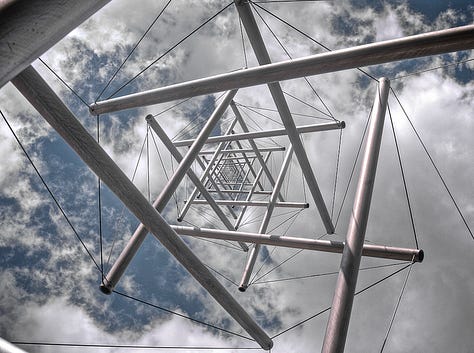

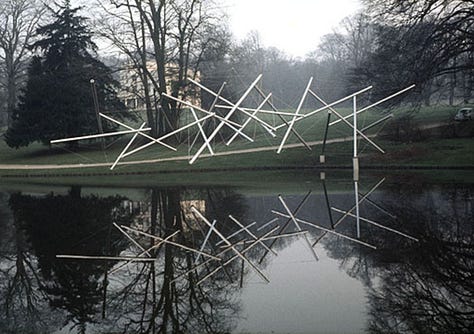

Tensegrity is a term coined by Buckminster Fuller—a contraction of "tension" and "integrity." It describes a structural principle that stabilizes form through continuous tension and isolated compression. Unlike traditional compression-based structures, like stone arches or skyscrapers, a tensegritous form is held together by the balance between flexible and firm components. Rods (compression elements) float within a network of tensile elements, creating a unified structure of surprising strength and resilience.

Fuller’s thinking was inspired by the sculpture of Kenneth Snelson, whose floating metal struts demonstrate the levity and elegance possible when tensegrity is at play. Most buildings stack load directly into the earth. In contrast, tensegritous structures distribute forces in all directions — making them flexible, self-supporting, and able to absorb stress without breaking.

Biotensegrity: Structure and Intelligence of the Body

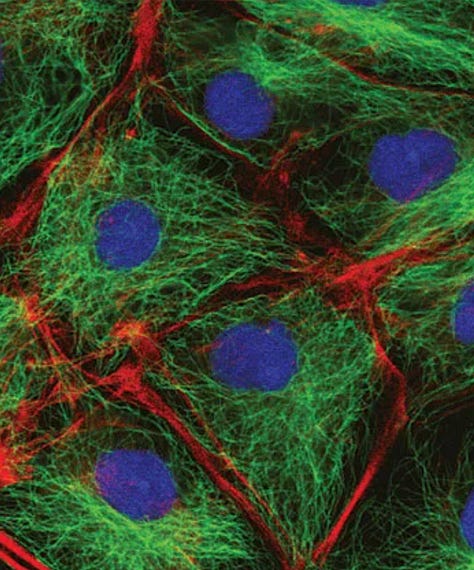

Scientists have observed these same principles in all living organisms. Dr. Stephen Levin coined the term biotensegrity to describe how biological systems—down to the cellular level — employ this distributed, omni-directional support. All living beings, from the tiniest cells to the largest animals, are structured through a dynamic balance of tension and compression.

At the cellular level, biotensegrity allows for sensation, adaptation, and biochemical change in response to mechanical forces. The same applies to fascia, muscles, bones, ligaments, and tendons. Rather than relying on fixed compression (like a skeleton stacked with muscles pulling on it), the body’s form and function arise from a continuous tensile web: a living matrix that both moves and perceives.

Levin writes: "It is impossible to explain the mechanics of a dinosaur’s neck using standard Newtonian Mechanics."

Fascia as the Tensile Fabric of Form

Fascia is the primary material expression of this tensegritous matrix. It surrounds and penetrates every structure in the body — bones, muscles, nerves, organs, glands. Fascia is beautifully not uniform; its densities and viscosities vary by function and location. It can be strong and fibrous or soft and pliable, depending on what the body needs in each area.

Far from passive, fascia is highly intelligent. Containing ten times more sensory nerve endings than muscle tissue, fascia communicates internally through impulses that travel at the speed of sound in water, around 720 mph — compared to about 150 mph through nerves. This means fascia senses, responds, and informs the whole body faster than the nervous system.

Fascia is also a system of interoception—our ability to perceive inner states. This interweaving of perception, form, and sensation makes fascia central to the experience of embodiment itself.

Bones as Floating Struts: A Shift in Paradigm

In the biotensegrity model, bones are not levers that hinge at joints. Instead, they are suspended within the fascial weave, like floating compression rods inside a tensioned network. Fascia integrates movement globally, not just locally. There are no pure hinge points — only flowing distributions of force.

This same model exists in cells. The cytoskeleton provides the compressive elements inside the cell. Its microtubules, filled with fluid, act as internal communication lines. A Nobel Prize-winning team of researchers once described the contents of microtubules as resembling "liquid light" — a poetic nod to the mystery and vitality within our cellular structure.

Cells are intelligent, autonomous units that sense, adapt, and act — not by brain command, but through their own membrane-contained awareness. The body is a community of such units, integrated through form and intelligence.

We learn to sense the world within through the unapologetically subjective science of yoga and somatic inquiry.

Fluidity, Communication, and Consciousness

Our bodies are mostly fluid, and our cells are geometrically designed for close packing and efficient force transfer. When pressure moves through one cell, that force is transmitted in all directions to surrounding cells. Fascia, as a fluid-rich, continuous weave, carries this transfer on a macro scale.

This capacity for instant, seamless, whole-body communication is not just mechanical. It’s deeply intelligent. Fascia doesn’t merely connect parts — it orchestrates their relationships.

How do I feel this, and what does it mean to my life?

Lets explore it.