THE THORACIC CATHEDRAL

The term “rib cage” is a bit harsh, don’t you think? Why in the world would we name this tender and perhaps sacred part of our bodies a cage? The name alone limits how we live within our thoracic region’s supple, strong, mobile, and resilient self.

Let’s call this beautiful and regal structure by a name that more befits its reality. Thoracic dome is certainly better. Maybe we can even go so far as to call it a cathedral.

The thoracic cathedral is the space and the home for our heart and lungs.

We can change our understanding and embodiment of this structure by learning more about it. Once we really get that it is not a cage, we can begin to alter how we breathe and live in the region of our hearts and lungs. Words matter. When we perceive our thoracic structure as a cage, we have a strong tendency to treat it like one. We tend to embody a much more rigid state than is actually offered.

For goodness sake…we are talking about the home of our hearts. Restriction in the thorax can limit so much about how we live, how we breathe, how we move, even how we mourn and love.

Let's remedy that.

THE ARCHITECTURE — THE BONES

Looking at, and feeling, how our thorax is constructed we find tremendous opportunities for articulation and effortless movement right at the level of bone. We actually see inherent soft strength and fluidity embodied within the bones and joints themselves. Let’s just start by noting the nature of our ribs and move on to the many, many joints.

First of all, we do not do not simply have twelve ribs attached to the sternum in the front, and the spine in the back. This particular image has given rise to the very commonly taught method of moving the ribs like "bucket handles" on the sternum in the front and the spine in the back. This is the version of breathing dynamics you and I both have probably learned. I can only say that I believe this image to be potentially damaging, not only to our breathing, but to how we live in our bodies in every way.

We are going to explore our thoracic cathedral in a very different way. With an astonishing number of joints and supple tissues, our thorax can actually move in hundreds of different ways. To define breathing as “ribs rising and falling like bucket handles” has pretty much nothing at all to do with the thoracic cathedral’s inherent possibilities for breath and movement. Nothing. Between the many joints and the soft tissues, the cathedral’s bones can move through soft undulating waves. Our ribs can ripple outward individually or together, like feelers or feathers.

Let’s take a look.

Henry Gray, the author of Gray’s Anatomy (originally published in 1858) described our ribs as “elastic bands of bone”. As we know, red bone marrow flows within our ribs. Marrow is warm. It is producing blood right inside our ribs. Might alive bones be more capable of movement than we commonly think? Most anatomical descriptions of ribs come from observing dead bones. Our bones are not dead.

For some reason we have completely ignored many of the smaller joints that are actually critical for freedom of movement in breathing. A few of us have counted 126 mobile joints in the thorax. Give or take.

Of course we are all different and have used our bodies differently over our lifetimes. The active number of points of articulation will be different for all of us as well. For myself, I definitely did not feel all these joints and movement capabilities right away! Having bought into the common and much more limited breathing and moving dynamics that I was taught, I was actually quite limited in my own embodiment. I am happy to say, that has changed. Our personal inquiry is all we need to open our bodies to their potentiality. This has definitely been true for me.

Let’s look at some of the anatomy images published by Henry Gray in the 1800’s (public domain) and see if we can help free our ideas about what is possible.

ANTERIOR THORACIC JOINTS

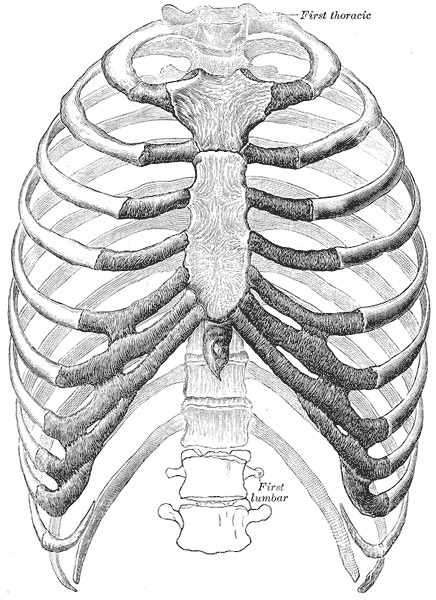

The image on the left shows the anterior (front) view of the thorax. We can see many joints.

—We have the three bones of the sternum: the manubrium, the body, and the xiphoid process.

—Particularly note the three separate sternal bones, their joints with the cartilage of the ribs, and then the cartilage of the rib’s joints into the rib bones.

—We have costal cartilage and costal bones (ribs).

—Important: Notice where the second rib’s cartilage comes into the joint between the manubrium and the body of the sternum. Look closely and you will see that on each side the cartilage is actually joining with both the manubrium and the sternal body. Two joints on each side.

The center picture shows where the collar bones joint with the manubrium (the top of the sternum). The collar bones joint here via a disk. The disk makes the collar bones particularly mobile on the sternum.

The image on the right is just for further clarification. If you happen to be a complete nerd for this stuff notice the interchondral synovial membranes between the lower ribs. (I am not counting them as joints, but they are synovial, which is significant.)

POSTERIOR THORACIC JOINTS

Each of the twelve ribs joints into the vertebral column. The ribs are very precise movers of our thoracic spines. Each rib has multiple joints with the vertebral column.

There are two ways we can think of how the ribs articulate with the spine.

—Where a single rib connects with two adjacent vertebral bodies (above and below) AND with the disk between them. This forms three distinct points of articulation. (The first image above.)

—Where the rib’s costal facet articulates with the vertebra’s transverse process.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN TO OUR EMBODIMENT?

It’s not at all about how many joints there are. It is about shifting our self-conceptions and opening to new possibilities. The suppleness of our ribs and their cartilages, the array of mobile joints around the front chest and into the back, and the sheer magnitude of the possibilities for movement and consciousness, give us plenty to contemplate and embody.

The most important thing is to open oneself to what is new. How we think is how we breathe and move. When we perceive our bodies and ourselves as more limited than they are, we remain stuck in that place. It isn’t hard to just ask a question. Might there be more than this thing I think I know? Opening to the possibility of new is the best route to freedom. We can do this in our bodies and it is contagious. It spreads.

INTERCOSTAL MUSCLES AND THE THORACIC DIAPHRAGM

Next time we will look at the intercostal muscles and how they too are little understood and utilized. Clue: There are three layers, each layer with its own angle of action between its own two ribs. This tremendous articular capacity of the intercostals assists our ability to individuate each rib’s movement, one from the other. It allows us to create both differentiation and harmony within the entire structure. This has dramatic effects on our breathing.

Then we will get right down into the nitty gritty of it with the thoracic diaphragm. Our thoracic diaphragms form the bottoms of our thoracic domes. The diaphragm gracefully integrates the seat of our hearts and lungs all the way through our deep bodies and into the root at pelvic floor.

SHORT BREATHING AND MOVEMENT VIDEOS COMING SOON!

Keep and eye out!

Thank you for being here to share with!

I so appreciate your presence and your interest.

Patty

Yes Camilla, Words do matter! We create an image in our minds and take it right into our bodies when we hear words.

It’s interesting to observe how we use our language, both internally and in in our speech as we go through an ordinary day. I find I am not always kind to myself. ❤️

Loving all this detail along with your very wise words. Thank you as ever,

Patty 🙏